How to talk about Black Lives Matter, Taeyoon Choi

I’m working through three challenges by writing this letter. First, I’m unlearning the racism in myself. Ijeoma Oluo, a Nigerian-American writer, in her 2018 book So You Want to Talk about Race1 wrote, “If you live in this system of white supremacy, you are either fighting the system or you are complicit. There is no neutrality to be had towards systems of injustice, it is not something you can just opt-out of.” Reflecting on her words and my experience as an Asian American in the U.S., I’ve been thinking through a painful process of reflecting on my inner complicity with racism and White Supremacy. In the recent unfolding of personal and professional events, I am beginning to see the structural racism and implicit biases in my community, both in the U.S and South Korea, in our spaces; schools, works, companies, communities, and the societies at large. Many South Koreans and Korean Americans I know think of themselves as racially-neutral, therefore not-a-racist. We turn to be self-defensive and talk about the ways we’ve experienced marginalization, discrimination, and racism. In our communities it is not uncommon to find racism if you are attuned to the forms in which it presents. If not, identifying racism can be enigmatic, and met with hostility. That is precisely the core of the problem: anti-Black racism permeates through all of our lives, and we don’t talk about it, at least until recently.

Second, I’m learning the importance of imperfect allyship. I’m borrowing the expression from Ashley Jane Lewis2, who I’m working with on a class about Teaching as Art at the School for Poetic Computation(SFPC)3. An allyship is a sense of togetherness among people who are oppressed and a sense of love across their differences. Just like how oppression and discrimination is never stable, allyship can not be perfect nor complete. An allyship is an ever-changing transformation. In seeking for an allyship that honors the arduous process of learning and unlearning, we can build the foundation to co-create a blueprint towards racial justice and anti-racism in our spaces. In this letter, I’m focusing on the allyship and solidarity between those who identify as Black, BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, Person of Color), and East Asians. I believe a similar kind of allyship can extend to White, European, South Americans and others, however, they are not the primary audience of this letter. The work that needs to be done to form an allyship between East Asians and the African Diaspora, that is, the unlearning that East Asians need to do towards racial justice, is so grand that I need to focus on writing about some particular conditions of injustice within our communities.

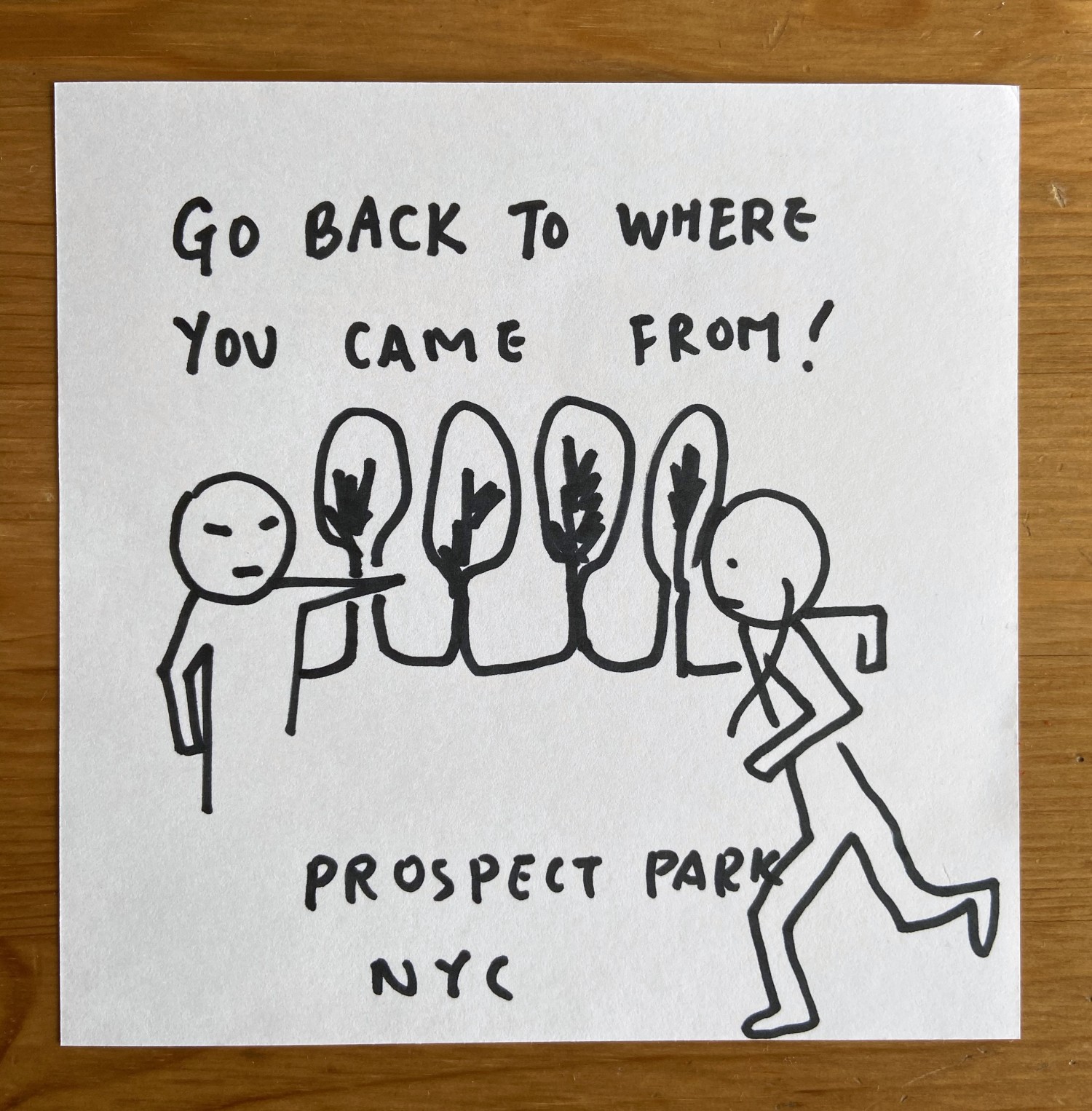

Third, I’m connecting the hyper-local issues with global patterns. I began to write this letter while I was relocating from New York City to Seoul between March and August of 2020, during the crisis of COVID-19 and uprisings in the US and UK regarding the police brutality against Black people. The issues of racial justice at hand are site-specific and must be discussed with sensitivity towards our positions within physical and social spaces. For example, how someone experiences racial tension in London or Seoul is different from Flint, Michigan, and New Orleans, Louisiana. The lived experience of blackness (read: anti-blackness) is pervasive, nonuniform, and varies along dimensions of skin tone, gender identity, ethnicity, nationality, or any other social conventions shaped by the vestige of colonialism. What do we, East Asians and Asian Americans, need to do to practice anti-racism in the local and global communities?

The conversations around racism in the U.S. have been changing very fast over the last few months with regards to the Black Lives Matter protests. Asian American community’s position in the movement have also been rapidly changing; those who begrudgingly acknowledge their identity as gentrifiers, those who work as advocates for social change through grassroots organizing and mutual support, those who identify as international students, resident aliens in various stages of immigration and integration, all hold distinct perspectives about the movement, their participation, non-participation or criticism of it.

There’s a scene in Spike Lee’s film Do the Right Thing (1989) which haunted me for years; a South Korean deli owner desperately screams “I no white! I black! You, me, same” to Black people in order to protect his business. That scene4 offers a glimpse of the East Asian and Black conflicts in the U.S. The racial conflicts continue back home as well, such as the recent controversy of South Korean High Schoolers posing in blackface or the long history of the U.S. Military presence, discrimination against Black and darker-skinned people, and culture White Supremacy in South Korea.

It’s challenging to map out the wide range of views about racism. I want to start from one common understanding. There’s a big change happening in the world now regarding racial justice, anti-racism, via Black Lives Matter movement and organizing, and the change needs to be understood in the context of social justice movements and ongoing violence against the marginalized communities abroad and at home.

Unlearning Racism

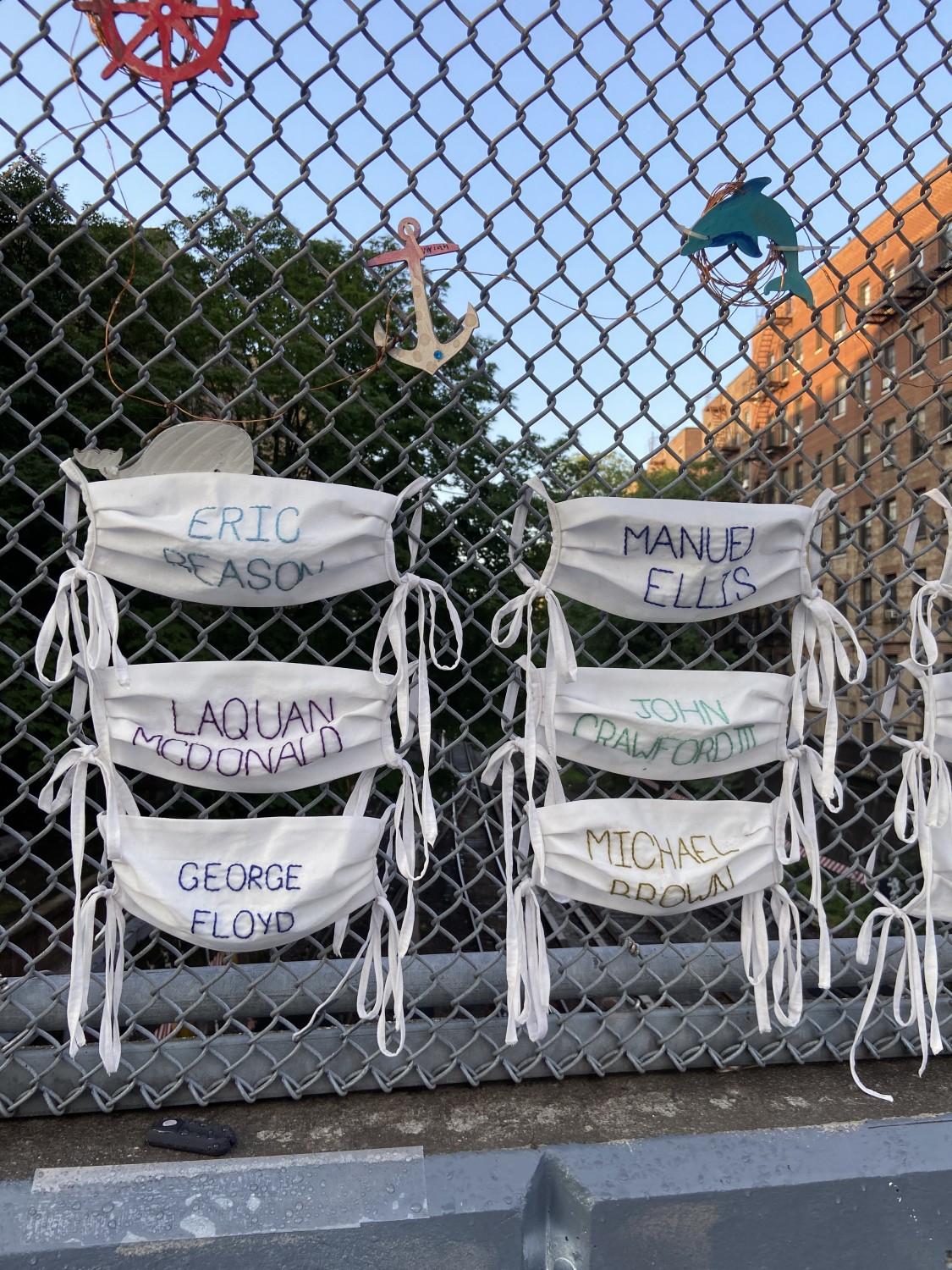

The deaths of unarmed Black people at the hands of the police in the United States, including George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, Sean Reed, and countless more were just a few in our global history. Such violence and systemic injustice are integral to the fabric of society and they are not only limited to the United States. Racial injustice needs to be traced back to colonialism and a global network of exploitation. It's a complex and large problem that we are a part of as both victims and beneficiaries. For the last few years, I’ve been advocating for “Diversity and Inclusion (D&I)” as an artist, teacher and activist. I’m realizing the optics of D&I are outdated, and can easily lead to the tokenization. Invitation into a space can be harmful if the space is not safe for the marginalized person. Recently there have been incidents of when conflicts surfaced and my community members have asked, “how can you propose to hold space for Black, Brown, Indigenous people of Color (BIPOC) if you are not personally committed to anti-racism in our interpersonal relationships?” I am troubled that I did not first ask myself. Most people think of themselves as good-hearted and therefore they do not consider themselves as slightly racist. They feel personally attacked when someone raises concerns about their bias, use of racial words, or their behavior. I too did not think of myself as a racist until reading Ijeoma Oluo’s book So You Want to Talk About Race. In response to her book, I wrote seven guidelines for my practice and daily life to demonstrate my own commitment to anti-racism both interpersonally and in practice.

─

-

Bear witness and support the oppressed: I will not stand still when a Black person is harassed, ignored, misrepresented, abused by others in classrooms, streets, my organizations. I will not tolerate any gestures that can make the person uncomfortable. In the event that I make a Black person uncomfortable, I will hear their voices and allies' criticism with a sense of gravity, apologize, and correct the course.

-

Demand anti-racism in my organizations: I will leverage my resources and network to demand anti-racism in organizations that I work for and that hire me. I will ask my coworkers, as well as clients and collaborators in the higher education, art, and technology field, to reorganize their leadership for Black and BIPOC people to have the agency and power to bring change, update their Code of Conduct and Mission Statement to address explicit anti-racism in their operations and community principles.

-

Support Black-owned institutions and organizations: While it’s important to bring racial justice to my organizations, it’s also important to support Black-owned galleries, artist-run schools, and institutions that are already practicing anti-racism and providing learning opportunities for Black communities. I will make financial contributions and encourage my community to support them and follow their work.

-

Build trust through transparency: I will assist racial justice initiatives by credible organizations and any organizations I’m involved with. I will work towards transparency in finances and decision making for racial justice initiatives. I will work openly by sharing the work in progress, inviting the allies and communities to collaborate, and will continue to welcome criticism.

-

Credit people: I will credit those who’ve helped or inspired my work in all publications in any way possible. In case of failure, I’ll edit and update. Also making sure they share in the financial returns of my work, should the opportunity arise.

-

Organize locally: I will explore what I can do locally in South Korea to fight racism and anti-blackness, such as writing about the issues in Korean, or helping local organizers with public events to build awareness, and form solidarity for anti-racism movements. I will continue the work that can be done remotely and systemically in the United States and throughout the SFPC’s international community. These words are meaningless without action. I will get to work.

-

Address intersectionalities: This list of actions focus on my relationships with Black community members in response to their request for a statement. These principles should not be isolated. Intersectionalities matter. I will extend the same commitment to other People of Color, People with disabilities, the LGBTQ, and Indigenous communities as well as those who are marginalized and underrepresented in my spaces. My actions are intended to recognize the humanity of those whose personhood is systemically and systematically denied, not to serve my ego. This is not a deed to do occasionally, or as an act of goodwill. It is my responsibility to deconstruct systems of oppression in each and every capacity I can.

─

I recommend the readers to think about how you can practice anti-racism in your interpersonal relationships and also your organizations. Writing your commitment is the first step towards building an allyship.

imperfect allyship

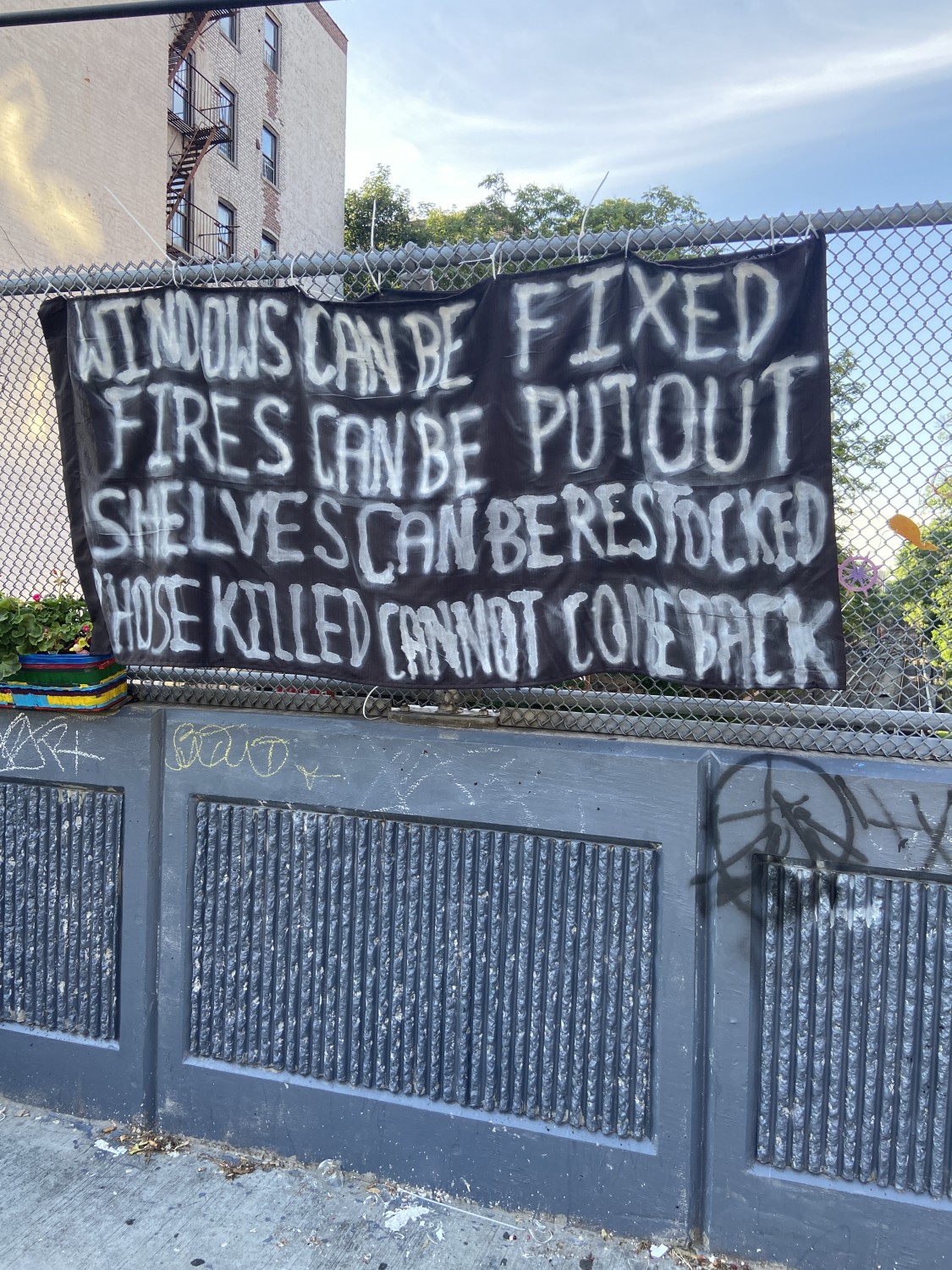

In the first week of June 2020, as the Black Lives Matter protesters marched in the streets in the U.S., I watched the South Korean press cover the events with great urgency. I found two points of failure in the press that favored dehumanization over allyship. My first point is about semantics. The press focused on civil disorder and looting – not the peaceful protests, the solidarity between different communities, the efficient mutual aid work, or how this movement relates to and challenges white supremacy. My Korean and Korean-Americans friends had a little understanding of the problems of racial bias in policing or the prison-industrial complex. Many were quick to draw the connections with the 1992 L.A. ‘riot.’ Among the activists and historians, there’s a debate about calling the events that took place in Koreatown LA in 1992 as ‘riots’, ‘uprising’ or ‘rebellion’ depending on how they view the context of systemic violence that led to the ‘riots’ in LA in 1992, New York ‘riots’ in 1968, Detroit ‘riots’ in 1967 and more. It’s true there was unauthorized vandalism, theft, and spontaneous violence against civilians and the police; I am not undermining or legitimizing the violence. However, calling the events as ‘riots’ flattens the movement and tells only one side of the story. The other side discusses a more complex web of the ongoing systemic discrimination against Black people: state-sanctioned violence and victimization, ghettoization and gentrification, displacement and racial exploitation. These moments, sparked from the ongoing violence against Black people, who have not only contributed to but formed the foundation of American prosperity, cannot be reduced to the immediate circumstances of civil unrest. When contextualized, we can critique the longstanding social order instead of those afflicted by it, and find global solidarity premised on mutual understanding and respect. A meaningful allyship is never a one way street, it’s a collaborative interdependence and mutual support between Black and non-Black people.

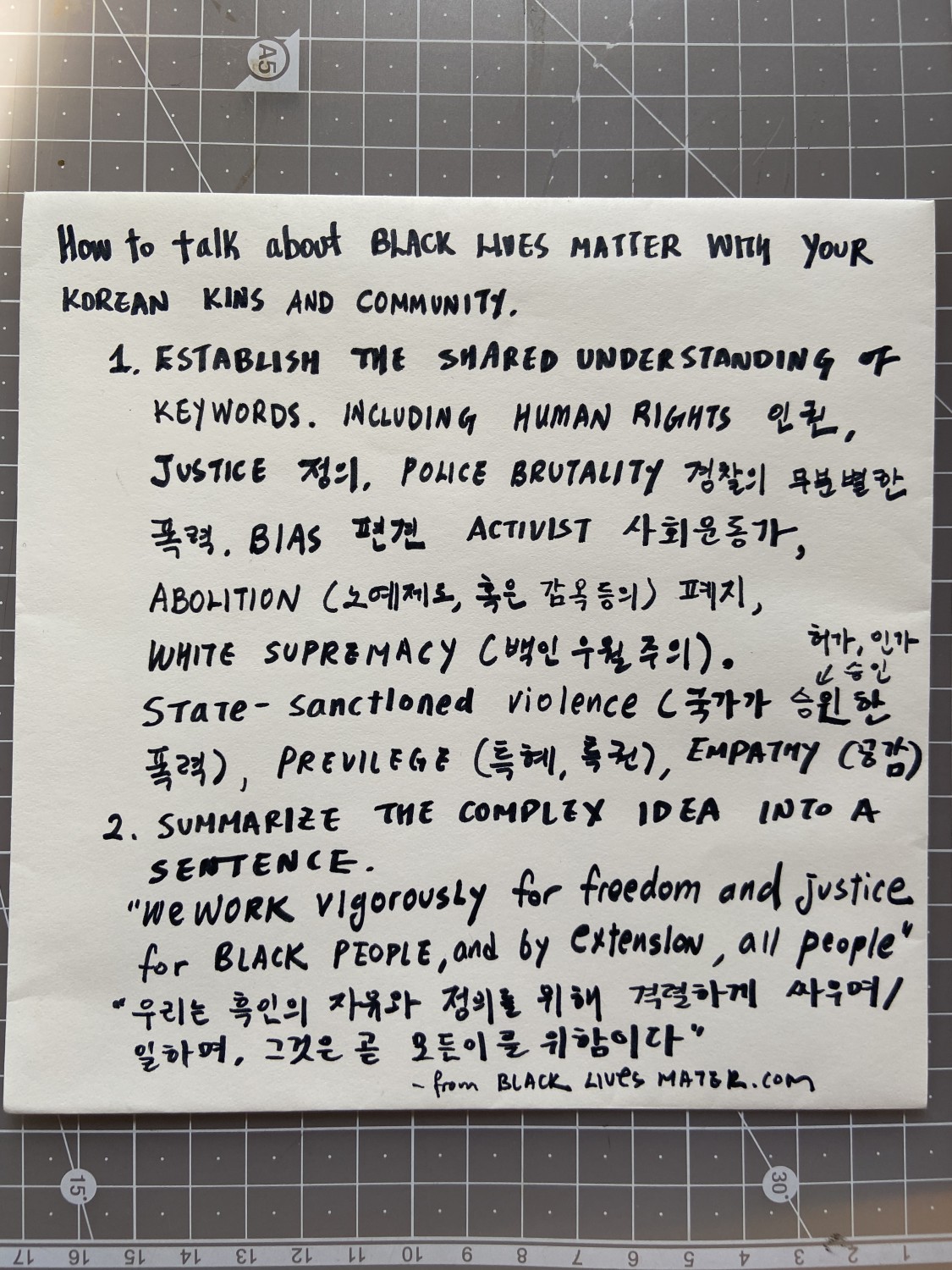

Second point is on mistranslation. Many of the South Korean press translated Black Lives Matter into Korean as “Black Lives also Matter” (흑인의 삶도 중요하다). That’s a grave mistranslation because it’s comparing the worthiness of Black lives in the context of ‘other’ lives by saying ‘also.’ This mistranslation is an example of centering Black Lives Matter on non-Black experiences. A more culturally sensitive translation would be “Black Lives Matter” (흑인의 삶은 소중하다) independently of comparison to other lives. The core message of the Black Lives Matter Movement is — a Black person’s life is worth living, that their dignity must be honored and their body and mind must be protected from police violence as well as the structural violence.

East Asians are a part of the systemic violence against Black people because of their complicity in White Supremacy. There’s a scene in the film Get Out (1997), where an Asian man participates in a silent auction for the Black protagonist’s body with other White people. The East Asian character in Get Out’s dystopia asks, “Is the African-American experience an advantage or disadvantage?” with a thick accent. He compares the Black experience with his Asian experience for a brief moment, and participates in White violence against Black people. This man is a familiar sight, Tou Thao, an officer involved in the killing of George Flyod, or Daniel Holtzclaw, or Peter Liang, or yet another asian sitting silently in the face of white supremacy. Our actions and inactions lead to structural violence and the lived experience of marginalized people. We need to care about it with compassion and commitment as if it is about our own life because we benefit and are burdened by a racist society.

East Asians experience various types of discrimination in our lives – there’s a history of exploitation and structural violence against East Asians in the U.S., like the Chinese laborers during the 1850 Gold Rush and the Internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Even with such history and continuation of racism against East Asians, we generally hold racial privilege over Black people in America. In general, an East Asian youth is less likely to experience stop-and-frisk on their way to school compared to Black youth. The same person may experience discrimination at a workplace, but we are less likely to be tokenized in the way a Black colleague may feel through their career. The East Asian person may live through a series of microaggressions and may feel difficult to integrate into society as an adult, but the East Asian are unlikely to feel threatened in all the ways a Black person is likely to feel in their everyday life. These experiences of racial privilege may influence the East Asian to gravitate towards Whiteness in search for an adjacency with White spaces. Academic prestige and employment at highly recognizable companies are means in which non-Whites can achieve legitimization within the bounds of White supremacy. These recognizable stereotypes of East-Asians reveal sites of submission to a white, patriarchal hierarchy. Through marriage and childbirth, East Asians reproduce our privilege and encourage our children to walk the path of least resistance towards Whiteness. East Asians in the U.S. often live in tightly-knit communities based on languages, religions, social class (what school we went to in our homelands or the U.S.), and business relations. East Asians are comfortable to exist in our own bubbles and choose not to engage with the local politics or inter-racial and inter-cultural solidarity. These cliché narratives are problematic, and charged with racist gaze on their own. However, it is useful to understand the general optics that the non-East Asians may view East Asians in order to unlearn towards the racial equity and racial justice.

To practice allyship, we need to become accustomed to decentering ourselves in some conversations about racial justice, in order to make space for voices that need to be heard. At this point in time, we need to focus on the Black voices and defend Black humanity. An allyship as an artist, curator, writer and cultural producer, begins by centering the Black experiences that are traditionally suppressed, and ignored from our art, culture and educational organizations. Decentering ourselves is not centering the work around our guilt or anxiety, which I find problematically common among White people’s performative reaction and participation in Black Lives Matter protests. To meaningfully decenter ourselves, we need to first identify our positions in society through the lens of power and seek out subtle, lasting, interpersonal commitment.

I’m noticing changes, among the younger activists and social justice organizers, especially in the LGBTQ communities like Authority Collective5, BUFU6, Yellow Jackets Collective7, and Press Press Baltimore8. There’s a movement towards a radical redefinition of East Asian Identities towards allyship with the Black Lives Matter movement to defy the stereotypes of the past, such as Letter for Black Lives9 (Korean Edition10). Artists, activists, organizers, shop owners in NYC, LA, along with other major cities in the U.S. and around the world are exploring many ways to protest against police brutality and systemic violence, support Black people and organizations, and demonstrate redistribution of their resources towards equity. For example, Skid Row People’s Market11 is a grocery store in Los Angeles run by the second generation South Korean immigrants. They are committed to bringing healthy food to the Skid Row community. Destabilizing whiteness, as queer-black feminist praxis does inherantly, leads to drawing connections between the wars abroad and at home, ongoing police brutality, slavery and carceral systems, gentrification and forced displacement, and racial capitalism.

If you are a non-White person, you are likely to be on the receiving end of racial discrimination in one way or another. To have a productive conversation towards racial justice, it’s not a good idea to recenter the conversation back to you by bringing up other discriminations you experienced based on race, gender, social class, or other factors. If you are decentering yourself in a meaningful way, it will take a lot out of you, painfully and slowly. The work may always be imperfect and you may need to get used to being criticized. Important changes are often painful and slow, but they are necessary and beautiful. Grace Lee-Boggs said “If we want to see change in our lives, we have to change things ourselves.” It’s our time to change. Perhaps that would be the beginning of an imperfect allyship.

Hyper-local context of South Korea

Hypothetical questions and answers.

Question: “I agree with the principle of equality and anti-racism. However, I live in a homogenous place and I do not know any Black or African people living nearby in South Korea. How can I connect and become an ally when it’s physically difficult to meet Black people and get to know them?”

Answer: It’s true, there are a small number of Black people in South Korea and East Asia. You may not know Black people in your life because you don’t make an active effort to diversify your communities. There are various Black communities in South Korea.

On the other hand, it’s common to find Black culture influence in K-Pop music, entertainment and fashion. Instead of cultural appropriation, you can attempt to meaningfully engage with discussions of Black cultural influence in K-Pop and streetwear, and collaborate with Black people in your field locally and abroad. It’s difficult to travel due to the COVID-19, but the mass communication, Internet and social network allows geographic limitations to become less determinant of our socialization and collaboration.

Combating anti-blackness includes destigmatizing people with darker skin within Asian communities. Popular obsession with pale skin is a symptom of colorism, a discrimination against people based on the color of their skin. In Korea, South East Asian migrant workers experience discrimination endemic in racial capitalism.

Question: “What can I do to become an ally?”

Answer: The most important and possibly the most challenging work towards allyship has been to have a conversation about race, racism, and racial justice with people around you. I began to notice the racism, white supremacy, anti-blackness, and lack of empathy in my friends and relatives. To speak about racism critically with my kins and community is incredibly difficult because I needed to begin by admitting my own racism, privilege, and complicity. I feel a sharp pain in my stomach when I have to speak about and admit the racism and bias that I inherited and propagated, unconsciously, or reluctantly by lack of action. However, speaking about it has given me a sense of connection with others who feel similarly, and that’s the beginning of an allyship.

Question: “What should an art institution based in Korea do?”

Answer: Do not replicate American and European institutions’ tokenization of Black artists, writers, and curators. Do not fall into the rhetoric of Diversity and Inclusion. There’s a certain type of ‘white-washing’ that happens in art institutions through Diversity and Inclusion initiatives. Jeff Chang in We Gon’ Be Alright highlights that, “Diversity allows whites to remove themselves while requiring the Other to continue performing for them.”

Instead, learn to listen, read, and as Detroit organizer Adrienne Maree Brown, wrote in her book Emergent Strategy, “Move at the speed of trust.” Jerrom Herman, a friend, and collaborator of mine said, “There are many ways to raise a fist” in his performance at the Whitney Museum in 2019. A sign in Flatbush, Brooklyn area where I used to live, said “If Black Lives Matter, All Lives Matter.”

Author: Taeyoon Choi

Artist, teacher and organizer based in Seoul and New York. He co-founded the School for Poetic Computation where he continues to organize sessions and teach classes on electronics, drawings, and social practice. In 2020, he presented a solo exhibition The Care of the Self: Diary and Letters at Factory2 in Seoul. https://taeyoonchoi.com

Editor: Iretiolu Akinrinade

Nigerian-American from Chicago who recently obtained a Bachelors of Science in Psychology. Her work aims to discuss technology and society centering Black-feminist praxis.